Pin-Up (Пін-Ап) виведення коштів

Українське онлайн казино Пін Ап працює за ліцензією КРАІЛ та пропонує лише сертифіковані азартні ігри, які працюють на ГВЧ. Вигравати у 100% випадках гравці не можуть, однак середній показник віддачі слотів у 96% дає непогані шанси на отримання винагороди. Pin Up гарантує чесний ігровий процес та своєчасну виплату грошей. Але останнім часом все частіше перед відвідувачами постає питання: Як вивести кошти з Пін Ап.

Чому не працює Pin-Up?

Причин, з яких не працює Пін Ап, може бути декілька:

- Технічні проблеми на офіційному сайті казино або платіжної системи.

- Pin Up не працює, бо спостерігаються проблеми з інтернет-з’єднанням гравця. Треба звернутись до свого провайдера.

- Доступ к облікового запису гравця обмежений за порушення правил. Це питання слід поставити оператору технічної підтримки.

- Шукаючи причину, чому не працює Пін Ап, слід перевірити, можливо доступ до казино блокує антивірус. У цьому випадку рекомендується його ненадовго вимкнути.

- Пін Ап не працює з причини порушення налаштувань DNS сервера.

- Обмеження доступу до Pin Up, бо відвідувач знаходиться у країні, юрисдикція якої забороняє азартні ігри. У цьому випадку слід скористатись дзеркалом, VPN тощо.

Тобто перш ніж звертатись у техпідтримку, щоб з’ясувати чому не працює Пін Ап в Україні, треба перевірити, чи проблема дійсно у казино.

Як вивести кошти з Пін-Ап?

З Pin Up вивести гроші можна лише за умови дотримання певних правил:

- обліковий запис повинен бути верифікованим;

- депозит та зняття коштів відбуваються з використанням одного рахунку, який належить гравцеві;

- перед тим, як подати заявку на кешаут, слід зробити хоча б одну ставку.

Покрокова інструкція як вивести гроші з Пін Ап:

- Авторизуватись на сайті казино. Ввести логін та пароль.

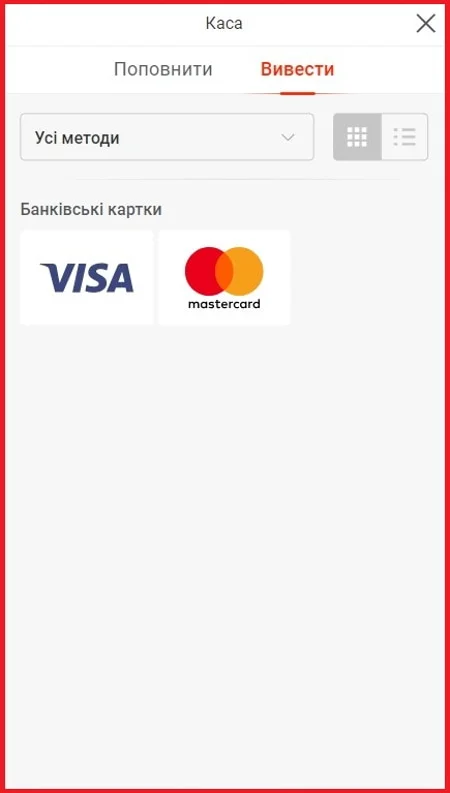

- Зайти у розділ «Каса». Розташований вгорі облікового запису.

- Перейти у «Виведення».

- Обрати платіжну систему. Раніше з неї повинен бути здійснений депозит.

- Вказати суму.

- Підтвердити переказ грошей, вказавши смс-код.

Слід врахувати, що Пін Ап є ліцензійним казино та утримує податок з виграшів при виводі. Мінімальний кешаут — 100 грн.

Що робити, якщо ви не можете вивести гроші?

Деякі гравці стикаються з труднощами при виводі та задаються питанням, чому не працює Pin-Up. У цьому випадку пропонується декілька кроків, які дозволять здійснити з Пін Ап вивід грошей.

Звернення в техпідтримку

Це перше, що повинен зробити гемблер у разі виникнення проблем. Спитати чому не працює Пінап можна цілодобово в онлайн чаті на офіційному сайті. Оператори відповідають протягом хвилини. Також відвідувачам пропонується написати запит на емейл або подзвонити телефоном. Додатково зв’язатись із саппортом пропонується у групах соцмереж — Телеграм, Інстаграм, Х.

Перевірте верифікацію акаунта

Нерідко трапляються випадки, що гемблер просто забув пройти верифікацію. Це обов’язковий крок для того, щоб мати змогу вивести гроші. Ідентифікація доступна у персональному кабінеті. Гравцеві необхідно надіслати копію одного з документів, що посвідчують особу, або пройти перевірку за допомогою застосунку «Дія».

Перевірка правил і умов

Перед тим, як зареєструватись та здійснювати фінансові транзакції необхідно познайомитись з правилами грального закладу. Азартні ігри та вивід коштів заборонені неповнолітнім. Також не можна створювати більше одного профілю. Деякі бонуси та участь в акціях мають додаткові обмеження виводу до моменту відіграшу отриманих виграшів. Більше інформації гравці знайдуть на офіційному сайті або дізнаються у оператора саппорта.

Виберіть надійний платіжний метод

Ліцензійне казино Пін Ап співпрацює лише з перевіреними платіжними системами України:

- Банківські картки Visa і Mastercard;

- Apple Pay Google Pay;

- City;

- Easy Pay.

Для виводу слід обрати ту саму платіжну систему, з якої був здійснений депозит. Якщо гемблер бажає змінити платіжний метод, то спершу треба поповнити рахунок.

Обмежте суму виведення

Розбираючись у питанні, Пін Ап чому не працює, треба спробувати знизити суму, яка поставлена на вивід. Може розмір виплати не відповідає встановленим лімітам.

Переваги гри у Пін Ап

| Плюси | Мінуси |

| ✅ Наявність ліцензії КРАІЛ | Вейджер для бонусів |

| 📞 Цілодобова підтримка клієнтів | Тривала верифікація |

| 🎨 Яскравий дизайн сайту | |

| 🎁 Щедрі бонуси | |

| 🎰 Більш ніж 6000 слотів | |

| 🏆 Якісна програма лояльності | |

| 💬 Велика кількість позитивних відгуків | |

| 🎉 Наявність бездепозитних бонусів | |

| 📱 Застосунок для Андроїд та iOS, мобільний сайт | |

| 🔒 Чесні умови гри, захист гравців | |

| ⚡ Швидкі виплати |

Висновок

Pin-Up — це одне з кращих легальних гральних закладів України, яке отримало позитивні відгуки від шанувальників азарту та гарну репутацію. Якщо у казино виникають проблеми з виводом, то труднощі швидко вирішуються цілодобовою підтримкою.

FAQ

🔉 Що робити якщо я не можу зайти на сайт Пін Ап?

У вас є 2 варіанти — це скористатись VPN дзеркалом сайту.

🔉 Де знайти актуальне, офіційне дзеркало Пін Ап?

Ви його можете самостійно запросити у техпідтримки, знайти на сайтах-партнерах, групах соцмереж тощо.

🔉 Чому Пін Ап усе частіше блокується у регіонах України?

Причина у тому, що керівництво закладу підозрюється у зв’язках з рф.

🔉 Що робити, якщо в мене заблокований вивід коштів?

Це можуть бути проблеми технічного характеру, проблеми з підключення до інтернету, обмеження доступу до облікового запису тощо. З’ясувати причину допоможуть оператори служби підтримки.